At New Year, I was reminded of how much heated argument can be generated when people have different views about what counts as knowledge. The reason for this was a program on Radio 4, The Two Cultures, that discussed the conflict that developed between the natural sciences and the humanities in the 1870's when the new scientific method, based on rational empirical inquiry, started to challenge traditional sources of knowledge, such as religion and philosophy.

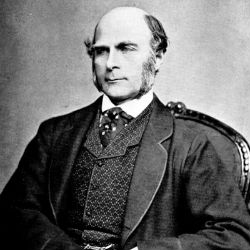

The seriousness with which many mid Victorian scientists took the view that the scientific method was the sole criteria for determining what counted as science was expressed clearly by Francis Galton (1822 – 1911) in an article in the Journal of the Statistical Society in 1877. The article argued for the abolition of Section F (Economic Science and Statistics) of the British Association for the Advancement of Science on the grounds that the topics debated could not be studied scientifically:

“Usage has drawn a strong distinction between knowledge in its generality and science, confining the latter in its strictest sense to precise measurements and definite laws, which lead by such exact processes of reasoning to their results, that all minds are obliged to accept the latter as true … we have to consider whether the subjects actually discussed in Section F do not depart so widely from the scientific ideal as to make them unsuitable for the British Association.”

I don't know how many leading statisticians would today agree with Galton's views about the social sciences. Galton's main interest was in the heredity of traits such as intelligence and it seems a little ironic to think that despite Galton's views of science as yielding 'definite laws', scientists are still vigorously debating the relative role of environmental and genetic influences on intelligence over one hundred years after his death.

The debate concerning what counts as an appropriate method has also been taking place within the social sciences since they became recognised as distinct subjects in the second half of the 19th century. Two of the most contentious points have been whether the social sciences should aspire to being scientific, both in the sense of being value free and in attempting to state universal laws. For some social scientists, subjects such as economics and sociology should be concerned with how people actually behave, while the study of how they ought to behave is appropriately a part of philosophy and politics. Other social scientists take a different view and see values as being an inherent part of the study of any social phenomena. While the place of values in social inquiry is likely to remain contentious there is now more agreement about whether the social sciences should seek to state universal laws, perhaps because with a very few exceptions, social scientists have found universal laws hard to find. The reasons for this are unsurprising. Human behaviour is too varied to be neatly described by universal laws while technological and social changes mean that society is itself constantly changing. The most that social scientists can claim is that the relationships they find are empirical generalities that appear to hold over a specific period and geographical context. The lack of universal laws does not mean, however, that all explanations are equally valid and statistics can and should be used to help us choose between competing explanations in the social sciences.

In order to illustrate the temporary nature of most laws in the social sciences we will quickly look at changing ideas about migration. Migration became an important topic in the Victorian era due to the development of an industrial urban society in which living and working conditions for many people were truly terrible. In 1885, George Ravenstein published an article on the 'Laws of Migration' in the Journal of the Statistical Society. The article compared the place of birth and the area of current residence of individuals using data from the 1871 and 1881 censuses. Ravenstein observed that the majority of non-natives in a town or county in a given year were born in adjacent counties and based on this his first law states: The majority of migrants move only a short distance.

Looking at recent data we would have to judge Ravenstein's first law as giving only a partial view of current migration patterns. While the majority of residential moves within England and Wales continue to be relatively short distance moves, changes in international migration have resulted in a significant proportion of the population in many areas having been born abroad. For example, the recently released data from the 2011 Census shows that population of the England and Wales rose by around 3.7 million over the last ten years with more than 50 percent of the increase being due to migration. The cumulative effect of international migration can be seen from changes over time in the proportion of the population born abroad. The figure above shows the proportion of the population born abroad for each region of England and Wales for all censuses from 1971 to 2011. The figure illustrates the sharp rise in the proportion of the population born abroad over the period, with the 2011 census recording over a third of Londoners as having been born abroad. Does this mean that Ravenstein's first law is wrong? The answer is neither yes or no, but simply that Ravenstein's first law doesn't appropriately reflect the opportunities for migration that exist at the start of the 21st century. In the future we may return to a situation where most people live relatively near to the area where they were born. But if that happens it is likely to be a result of either changes in the cost of travel or the political choices we make, rather than the operation of any natural law.