'Women and Children First' is a universal principle, and deeply ingrained in the human psyche. We protect the vulnerable, and the next generation. But was ‘Women and Children’ counter-productive? Did obeying the safety-rules hinder, or help? Would more have survived the Titanic if instinct – and decency – had been abandoned, and rules left to fend for themselves?

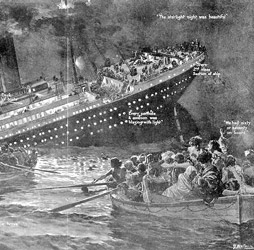

The Titanic struck her iceberg at 11.40 in the evening of 15th April 1912, a hundred years ago this week. The first lifeboats from each side of the ship departed half-empty: few at that stage believed the Titanic would actually sink.

An hour and a half later things were very different. Boat 13 was one of the last to leave. By then competition for a place in the boats was desperate. Steward Littlejohn was on A deck, helping to load that boat. Thirty-five women and children were onboard. ‘We shouted for more women. But there were none forthcoming’ he said.

At least 160 women and children were still on board; but there were no more immediately to hand.

Second Officer Charles Lightoller, supervising lifeboats on the port side of the ship, enforced the ‘Women and Children’ rule as strictly as he could; they were very few male passengers on his boats. First Officer William Murdoch on the starboard side, helped by officer James Moody, was less rigid. ‘I dont think he ignored the rule’ says Philip Littlejohn, steward Littlejohn’s grandson and author of a book ’Titanic – Waiting for Orders.’ ‘It was certainly not first come first served. He got the women on first; but after that he was flexible.’

Into Boat 13 he put one male passenger, Dr Dodge, from First Class; several third-class males including some Swedes, emigrants presumably; a Chinese laundryman; and a 14-year-old boy who had been refused admission to two women-and-children boats already. At the last moment Officer James Moody ordered two stewards to get in and help row it. One of the stewards was Littlejohn. And so he survived.

Rules are clearly good things; they are intended to save as many people as possible, and the most vulnerable first; and we should all obey them. But rules are made in advance; they cannot take into account the different circumstances of each disaster.

More people got off the Titanic from the starboard-side lifeboats, where Murdoch had been flexible, than from the ones on the port side of the ship where Lightoller had strictly ensured no queue-jumping. The figures are four hundred and sixty-one versus three hundred and ninety-nine.

The last lifeboat of all had room for forty-seven; 1,500 were still on board. The crew linked arms around it to keep back the desperate melee; and passed only women and children though. Duty done, the lifeboat cleared, Second Officer Lightoller walked into the water which was lapping at his feet. James Moody must have done much the same – he had already turned down an officer’s place in a boat. Neither probably expected to survive.

Lightoller was plucked from the water. Moody was not. ‘The crew, for the most part, all attended to their duties to the last, and until the boats were all gone’ says the official report. And the band, they say, played Nearer My God to Thee as the ship went down.