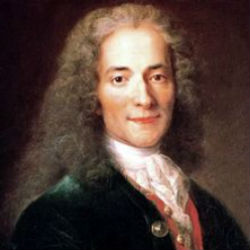

I was listening with half an ear (as one does) to Melvyn Bragg’s academic-intellectual-historical-philosophical-scientific educate-us-all-in-things-that-every-civilised-person-ought-to-know-but-probably-doesn’t programme on Radio Four yesterday, (and I think it is wonderful by the way). It was on Voltaire (1694-1778 as Melvyn was careful to inform us); and one of the experts gave us a little throwaway remark. ‘Voltaire became rich early in life by teaming up with a statistician to win the French national lottery.’ That was it.

Statisticians know about lotteries – see here for a video and here and here if you don’t believe me – but these days teaming up with one – even going to bed with one – will not guarantee that you win the jackpot. Today’s statisticians seem sadly to have lost that knack. But a little internet research threw up a bit more about Voltaire and his statistician and their coup.

The lottery in question ran from 1728 to 1730 with the aim of raising money for the government. It seems though that the French government of the time miscalculated, rather badly, and was offering a sum in prize money that was greater than the total amount they could hope to raise in ticket sales, even if every ticket was sold. Voltaire and his collaborator spotted that this gave them a large mathematical advantage, so they bought up as many of the tickets as they could. I don’t know if they cornered the market in them, or just struck lucky; at any rate, they won. Voltaire’s share was over a million francs; he never had to work for his living again and was free to spend the rest of his life alternately sucking up to kings and writing satires like Candide exposing the shallowness and futility of the whole caboodle. Candide involves, among other things, a heroine who has one buttock sliced off to feed her starving companions; and a nerdy philosopher by the name of Doctor Pangloss who maintains that everything is for the best in this best of all possible worlds – a slightly optimistic forerunner of the mulitiverse theory?

So who was this rather useful statistical friend of Voltaire’s? His name was Charles Marie de la Condamine. De la Who, I hear you cry? He ought to be a lot more famous than he is. As well as being a mathematician-cum-statistician he was an explorer of the Amazon, and a geographer. And he was the man who disproved the theory that the earth is round.

Having helped Voltaire to win the lottery (I assume they split the winnings) he sailed as eventual leader of a French expedition to what is now Ecuador. (In fact they gave the place its name. It was then known as the Spanish Vice-Royalty of Peru, but expedition members got so fed up with having to write all that on their letterheads and reports that they substituted ‘Ecuador’ – ‘Equator’ in Spanish – instead.) The object of the expedition was to see if the earth was round. It was suspected that it was not. People knew by that time of course that it was not flat, but opinion was divided as to whether it was perfectly spherical, or flattened a bit from the top – as if someone had pushed the north and south poles together – or sideways.

Having helped Voltaire to win the lottery (I assume they split the winnings) he sailed as eventual leader of a French expedition to what is now Ecuador. (In fact they gave the place its name. It was then known as the Spanish Vice-Royalty of Peru, but expedition members got so fed up with having to write all that on their letterheads and reports that they substituted ‘Ecuador’ – ‘Equator’ in Spanish – instead.) The object of the expedition was to see if the earth was round. It was suspected that it was not. People knew by that time of course that it was not flat, but opinion was divided as to whether it was perfectly spherical, or flattened a bit from the top – as if someone had pushed the north and south poles together – or sideways.

De la Condamine’s expedition was to measure the lengths of degrees of latitude at the equator. Another expedition was sent to measure degrees of latitude in Lapland. And comparing the two sets of measurements would settle the original question.

De la Condamine spent ten years in South America on his measurements. The team members quarrelled bitterly – even refusing to share their data with each other; they ran out of money – de la Condamine presumably spent the remnants of that lottery money keeping it afloat; they were accused of spying, their botanist lost five years worth of his collection; eventually de la Condamine came home, alone, in what must have been a remarkable voyage down the river Amazon, the first scientist, as opposed to mere explorer, to visit the region. The Lapland team had finished years earlier. The equatorial measurement, when it was eventually calculated, was greater. It meant that the earth is not perfectly round, but is flattened on top like an orange.

And De la Condamine’s measurement of a degree of latitude settled also of course the length of the circumference of the earth round the equator. And that in turn helped determine how long the French standard of measurement, the new-fangled metre, should be, since it was defined a few years later by Napoleon’s scientists as one ten-millionth of the length of the earth's meridian. So anyone who measures anything owes quite a bit to De la Condamine.

What happened to them all? De la Condamine, having been instrumental in determining the metre for posterity, went to Italy and spent his declining years in measuring Roman ruins in order to statistically determine the length of the ancient Roman Foot (the distance measurement, not the part of the anatomy – Latin pes, plural pedes.) 5 Roman pedes made a passus, the distance covered by a pace of a soldier on the march; and a thousand paces, or 5000 pedes, made a mile. The current best estimate of a pes is .296 of a metre, so a Roman mile was 1.48 km or .9196 of a current UK or US mile. Voltaire took as a lover Emilie du Chatelet, an extraordinary mathematician (how many female mathematicians were there in the 1740s?) who translated Newton’s Principia into French; then he retired to a pleasure-mansion at Ferney, and wrote Candide.

What happened to them all? De la Condamine, having been instrumental in determining the metre for posterity, went to Italy and spent his declining years in measuring Roman ruins in order to statistically determine the length of the ancient Roman Foot (the distance measurement, not the part of the anatomy – Latin pes, plural pedes.) 5 Roman pedes made a passus, the distance covered by a pace of a soldier on the march; and a thousand paces, or 5000 pedes, made a mile. The current best estimate of a pes is .296 of a metre, so a Roman mile was 1.48 km or .9196 of a current UK or US mile. Voltaire took as a lover Emilie du Chatelet, an extraordinary mathematician (how many female mathematicians were there in the 1740s?) who translated Newton’s Principia into French; then he retired to a pleasure-mansion at Ferney, and wrote Candide.

And after that, we should cultivate our gardens.