What does data show us about female representation in UK democracy? An exploration of gender imbalance in candidacy, and equality, diversity and inclusion mentions in party manifestos, in the 2024 UK general election.

Two important issues in British politics are achieving parliamentary gender balance and having political parties which prioritise equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI). The importance of gender balance has been addressed by The Fawcett Society, a UK charity campaigning for gender equality and women’s rights. Their research also shows that increasing the number of women active in politics contributes to improved decision-making, increased cross-party collaboration, and a general enhancement of democracy. The House of Commons Inclusion and Diversity Strategy for 2023-2027 is centred around decreasing the ethnicity pay gap, improving accessibility and fostering inclusive environments. Here, we quantify the performance of the political parties on these two issues in the context of the 2024 UK general election (GE2024).

Gender imbalance

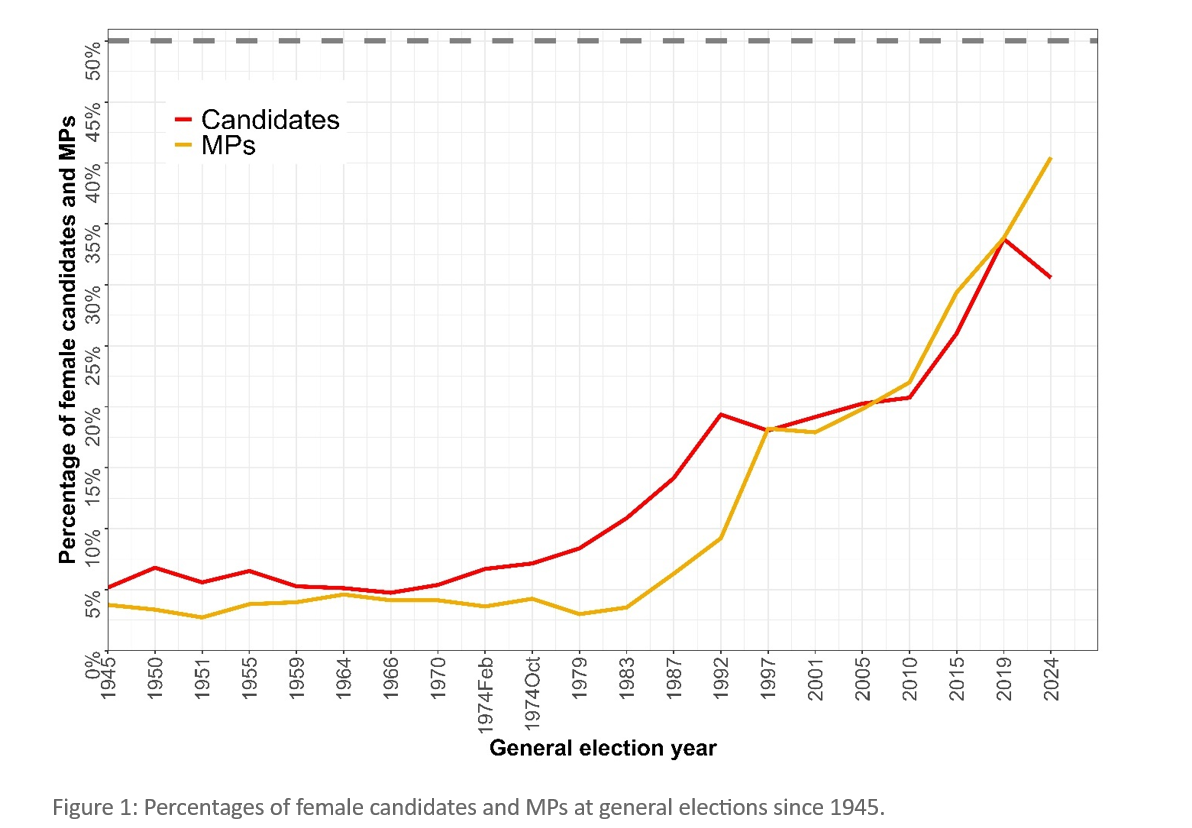

There has been an encouraging trend to correct gender imbalance in the last four UK general elections, with the percentage of female MPs increasing from 22% in 2010 to 40.5% in 2024. Despite this, the UK is still failing to achieve gender balance in parliament. Data from the Inter-Parliamentary Union and UN Women in 2023 showed that 27 countries were performing better than the UK. One explanation of this imbalance can be sought in data related to the number of female candidates.

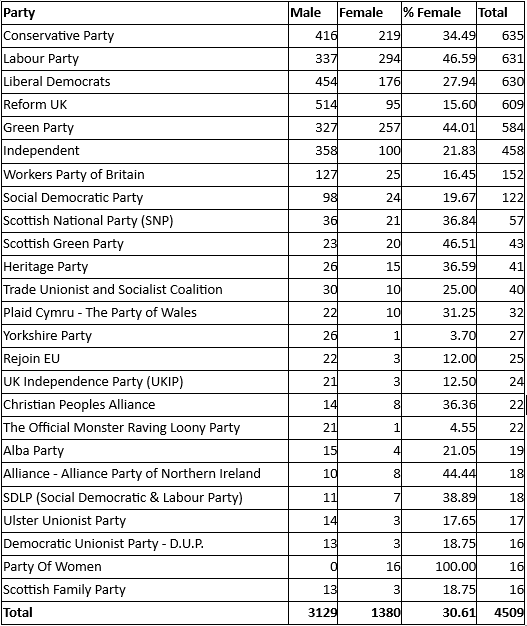

We obtained data from the House of Commons on the number of women MPs and overall number of women candidates since 1945 and from the Democracy Club on the 4,515 candidates from 99 political parties registered to participate in GE24; we merged the Labour and Cooperative Labour parties. Unfortunately, this data set does not include gender, so we allocated it according to first name and searched online for information to validate our assignment. We were unable to assign gender for six candidates; thus our dataset consists of information on 4,509 candidates of whom 1,380 (30.6%) were female and 3,129 (69.4%) male.

Figure 1 shows the percentages of female candidates and MPs in general elections from 1945. After 2010 the percentage of female MPs was greater than the percentage of female candidates, whereas this was generally not the case up to 2010. As mentioned, the percentage of female MPs has increased, from 22% in 2010 to 29.4% in 2015 and 33.8% in 2019, in line with the increase in the number of female candidates. However, in GE2024 the percentage of female candidates fell to 30.6%, while 40.6% of MPs are female, meaning that the gap is now larger.

Table 1 shows number of candidates by party and by gender in GE2024 for parties with at least 15 candidates.

Focusing on the five largest parties, we see that the Liberal Democrats and the Conservative Party are close to the national average of 30.6% female candidates. The Green Party and the Labour Party had over 40% female candidates, while Reform UK had 15.6%.

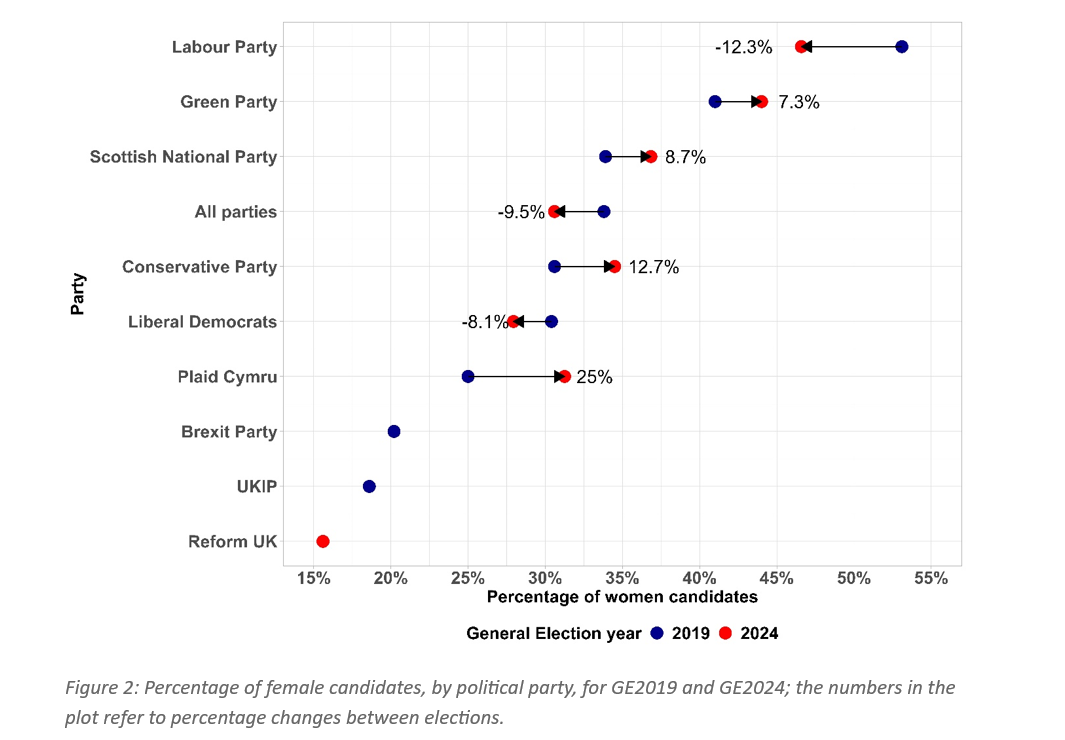

In Figure 2 we compare the changes in percentages of female candidates among the main parties between the 2019 and 2024 general elections using data on GE2019 from the House of Commons report and analysis . The parties appear in descending order of their percentages of women candidates in GE2019, and the numbers inside the plot are the percentage change from GE2019 to GE2024. Overall, there was a 9.5% decrease from 33.8% to 30.6% in the percentage of female candidates, although this differs across parties. The Labour Party and the Liberal Democrats had decreases of 12.3% and 8.1%, contrasting to increases for all other major parties, especially the Conservatives (12.7%), the Green Party (7.3%) and the SNP (8.7%). The Brexit Party (2019), UKIP (2019) and Reform UK (2024) had the lowest percentages of female candidates.

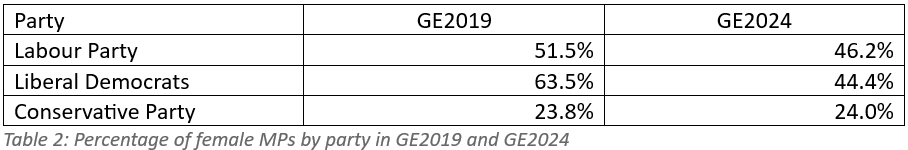

From Table 2 we see that among the three parties competing in the largest numbers of constituencies in 2019 and 2024, the Labour Party and the Liberal Democrats had smaller percentages of female MPs in GE2024 than in GE2019. Although the Conservative Party had a small increase in its percentage of female MPs, this percentage is lower at around 24%. The results for the Labour Party and the Liberal Democrats chime with the Fawcett Society’s analysis of gender differences across so-called winnable seats, defined as those constituencies where a party had more than 30% estimated chance of winning. Their analysis concludes that around 40% of women candidates were selected for winnable seats in 2024, a figure which seems to be corroborated in seats won by the Labour Party and Liberal Democrats but not among the Conservatives. This suggested that female candidates for the Conservative Party were more likely to stand for seats that they are less likely to win, compared to their male counterparts.

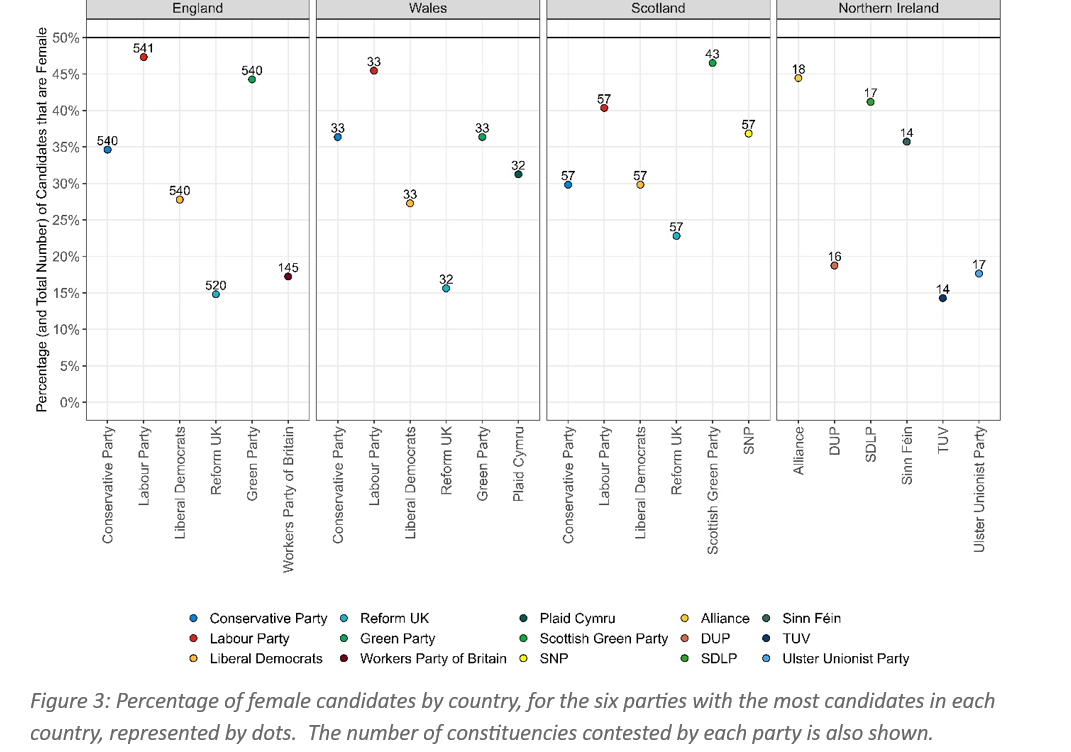

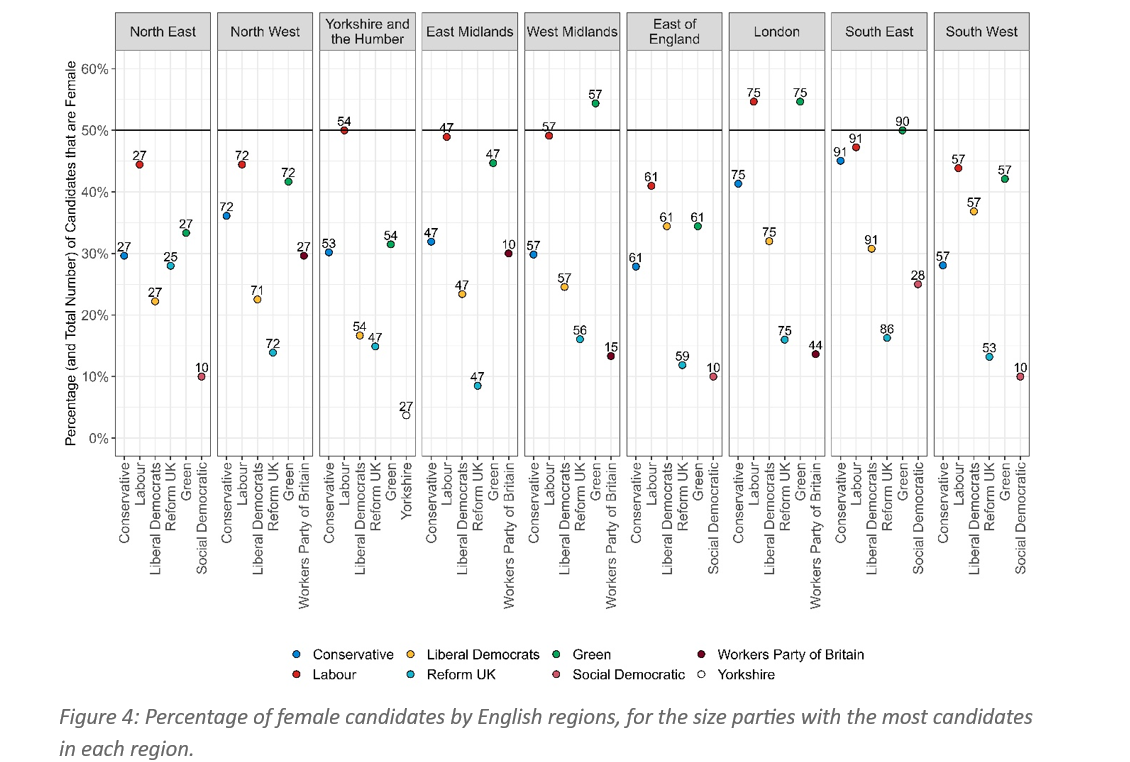

We now turn to the gender distribution of candidate by constituencies. There were 52 constituencies (8%) where all candidates were male. Figure 3 shows the percentage of female candidates by UK country, for the six parties with the most candidates in each country. We see a consistent picture across countries that females candidates are under-represented. There are regional differences in gender representation among the nine English regions, as shown in Figure 4. The Labour Party and the Green Party had close to or over 50% female candidates in London, West Midlands and the South East. The Conservative Party, which averaged around 35% female candidates, has above this average female representation in London and the South East. Reform UK averages 15% female candidates across England apart from in the North East, where this statistic is close to 30%, almost double the party’s average. The Liberal Democrats have over 35% female candidates in the South West, although this is less elsewhere. We now consider whether there is some relationship between these findings and the emphasis given to EDI in party manifestos.

Party manifestos and EDI

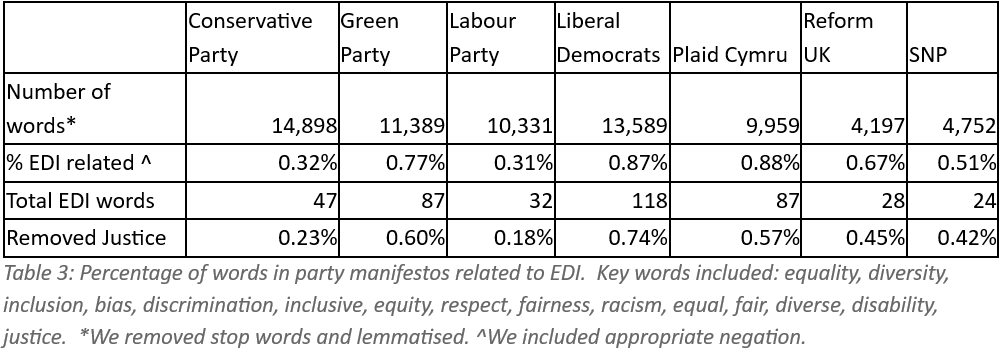

We obtained manifestos from the websites of the five major parties in the UK and of the parties with the largest number of contested constituencies in Wales and Scotland. Results from mining these manifestos for words related to EDI are presented in Table 3.

Overall, EDI-related words were rarely used in manifestos as they comprised less than 1% of words. Since “justice” was used frequently in a criminal justice context, we also present percentages with “justice” removed. Of the resulting percentages, the Liberal Democrats had the highest, followed by the Green Party. The Liberal Democrats were the only party that explicitly outlined policies to reduce gender inequalities. Other parties, for example Plaid Cymru and the SNP, referred specifically to gender health inequalities and gender pay gaps. EDI-related words were discussed in different contexts across manifestos. For example, the Conservative Party and Reform UK devoted text to justifying why they were proposing to limit or scrap all UK EDI-related activities.

Final remarks

Gender equality has been a strong priority for EDI strategies for the last decades in the UK, to the extent that some have argued that it has overshadowed other issues such as class and ethnicity. Despite this gender focus, we have not seen proportionate gender representation in the House of Commons. Also, all aspects of EDI receive limited attention in manifestos.

In GE2024 females continued to be under-represented in terms of both candidates and MPs. There are, however, some hopeful signs. We encourage political parties to pursue policies that lead to greater discussion of EDI-related issues and increased female representation.

Joseph Lam is a PhD student and research assistant in the Population Policy and Practice Teaching and Research Department at the Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, University College London.

Julian Stander is associate professor in mathematics and statistics in the School of Engineering, Computing and Mathematics, University of Plymouth.

Mario Cortina Borja is professor of biostatistics in the Population Policy and Practice Teaching and Research Department at the Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, University College London.

You might also like: Post Office scandal: prosecutions data should have been a red flag