Several years ago, my then 16 year old sister proudly announced that she had chosen her secondary school specialization – humanities. She was happy, she said, that – given her choice – she would never again have to wrangle with numbers. I warned that might not be the case; that statistics would soon make its presence felt. She demanded to know why, when and how, but at the time I didn’t have the answers for her.

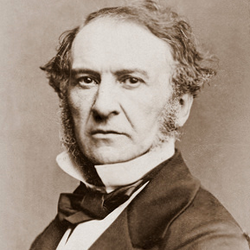

Now that she is a classics student I do have an example to share, and it is all thanks to Guy Deutcher's marvellous book, Through The Language Glass: Why the World Looks Different in Other Languages. Its first chapter tells us about Sir William Ewart Gladstone, politician and prime minister, who had a passion and scholarship for ancient Greek poetry. Gladstone also had an appreciation for statistics, and was president of the Royal Statistical Society from 1867 to 1869. Thanks to these dual interests he discovered that the Homeric poems – the Iliad and the Odyssey – were, in a sense, written in black and white. Or almost.

Before his first of four stints as prime minister (beginning in 1868), Gladstone spent some of his time as a member of parliament pouring through Homer's poems and writing three brick-thick volumes of his Studies on Homer and the Homeric Age (Vol. 1, Vol. 2, Vol. 3), published in 1858.

The book is a nitpicking analysis of all kind of subjects, from ethnology and religion, to geography, politics and language, and the role of woman in ancient Greece, as could be deduced from Homeric poems. Among these varied subjects, he addressed Homer’s use of colour in a systematic and statistical way. He counted each and every word used to indicate colour, registered how it was used and classified it.

| Ancient Greek | English | Number of appearances in Homer's poems |

| μέλας | Black | Approx. 170 |

| λευκός | White | >100 |

| πορφύρεος | Violet | 23 |

| ἐρυθρός | Red | 13 |

| ξανθός | Yellow | 10 |

| μίλτος | Ochre | 2 |

| ῥοδόεις | Rose | 1 |

| χλωρός | Green | 1 |

Table: Number of appearances of colour words in Homer's poems, according to William Gladstone. Compiled from the text of Gladstone’s 'Studies on Homer and the Homeric Age', Vol 3, Chapter IV – AOIDOS, Section IV – Homer’s Perceptions and Use of Colour.

Thanks to his detailed analysis, Gladstone noted some curious facts:

- Homer used very few colour words in comparison with modern usage. Note that in the table above there is no orange, nor blue, nor many other hues.

- Homer seems to use the same word for different colours.

- The same object is described with disagreeing and unexpected colour words.

- By far, black and white are more frequently used than any other colour.

- Colours are used for descriptions more rarely than we would expect.

Classics scholars had previously argued that Homer’s use of seemingly strange expressions, which had been translated as 'green by fear', 'green honey', or 'violet-coloured sheep', were the result of poetic license. However, Gladstone argued instead that the Greek linguistic colour system was not well developed at the time of Homer’s writing, in the 8th century BC (see here for a dating based on evolutionary-linguistic statistical methods). Many colour words did not have the same meaning that they would later acquire and most were used to mark the distinction black/white or, rather, dark/clear. Let’s take, for example, the word chloros, that would later mean 'green' (like in chlorophyll). Although it appears several times in the poems, according to Gladstone it denotes greenness only once and more likely meant 'pale' or 'fresh' in Homer’s day. Certainly, 'pale by fear' and 'fresh honey' make more sense. And the phrase 'violet-coloured sheep' was probably used to indicate the dark colour of the wool.

Gladstone put forward the hypothesis that there was something wrong with the eyes of ancient Greeks, that they suffered from some kind of colour blindness, and that the capability of discriminating colours evolved only later in human history. We now know this is not true: it was not the eye, but language that needed time to evolve. Later research (well described in Deutcher's book) showed that it is a common phenomenon in many languages. Like the evolution from black and white to Technicolor films, a similar change takes place in language.

In defence of Gladstone, he did acknowledge that more research was necessary. He wrote: 'I am conscious that the subject, which is now before us, in reality deserves a scientific investigation, which I am not capable to affording to it'. But while his interpretation was wrong, the facts he observed – that the Greek linguistic colour system was not well developed – was true, and opened the door to an interesting line of research on the evolution of language and on the perception of colour.

So there you have it – even classics students can’t escape statistics. Although, having checked the classics program at my sister’s university, I’m afraid to say that there’s no statistics module. More’s the pity.

Acknowledgements

- I thank my sister Cinta Prats for her help with ancient Greek.