Statistical evaluation of technology is nothing new – but the level of autonomy that AI models seek is. How can the statistical professions adapt to a world powered by AI? Here’s why 2026 could be the year of the AI phronestician…

Data scientists and statisticians are no longer needed. The sexiest job of the 21st century is out and all you need is an API key to have your own 24-hour on-call data scientist.

Or so you may be led to believe by a recent Microsoft research paper that highlighted the top 40 jobs with a high “AI applicability score” (data scientist was 28th). How can data exploration, careful study design and statistical methods compete with an army of round-the-clock agents promising to obligingly take ideas to fruition in a matter of hours for a few dollars?

This is wonderful when there are minimal consequences for being wrong; an AI poem can’t hurt anyone (beyond the sensibilities of poetry critics), but an AI with responsibility for cancer diagnosis could have tragic impacts. In the race to keep up with the weekly releases of benchmark-beating LLMs, there is little space for the statistical calm needed to answer the question ‘Is AI making things better?’ As we begin to entrust AI with the autonomy to make consequential decisions, we are in critical need of a newly skilled profession devoted to evaluating models during development, validation and post-deployment. Statisticians and data scientists are uniquely positioned to form the foundation of this new profession, and to challenge models that can look persuasively omniscient.

Evaluating technology is not a new problem, but giving decision-making power to a stochastically behaving system offers unique challenges. AI algorithms are not liable like regulated professionals, their effects are not consistent over time like a pharmaceutical intervention and their outputs are not explainable like traditional software. While these models are highly capable, the argument that “a black box doesn’t need to be understood to be safe, it just needs to be accurate” falls down when a system fails and somebody needs to be held accountable. This is a growing concern given the relatively few number of samples in a dataset needed to “poison” existing models.

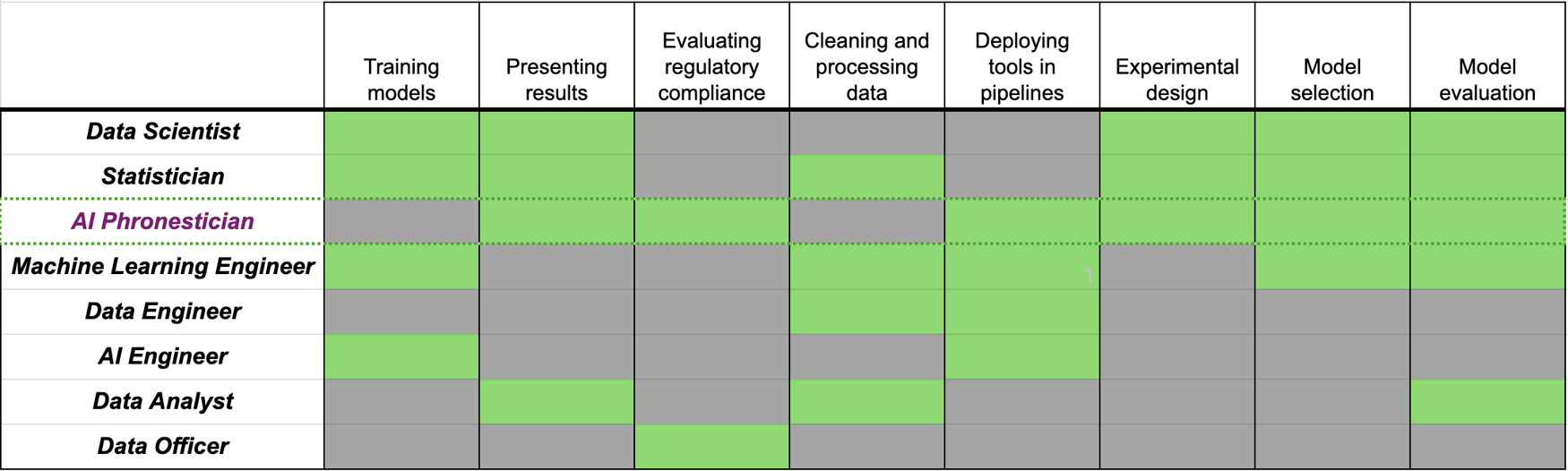

We are advocating for a new statistical professional – the pharmacist responsible for dispensing the AI medicine, especially important in situations where outputs have consequences and risks are high. This role brings together statistics, computer science, information governance and data ethics. We believe that this specific combination of responsibilities does not currently sit within a single job function, meaning responsibility gets diluted and models may be under-scrutinised (see Figure 1). While job roles vary widely in this field, we feel there is a case for defining such a new role, placing model evaluation at the core of its duties.

Any new field needs a new name; we take our inspiration from Aristotle, who defined phronesis as “the intellectual virtue that helps turn one’s moral instincts into practical action”. Such skills aptly describe our new profession, which we will dub the AI phronestician. Now, let’s explore what challenges they will need to solve.

Figure 1. The core responsibilities of some of the most common job titles in data science and machine learning. In practice, many jobs will fulfil other tasks outside of these “core” ones. As job responsibilities can vary widely in practice, we believe it is important to promote a role with model evaluation as a core responsibility when deploying AI models

Figure 1. The core responsibilities of some of the most common job titles in data science and machine learning. In practice, many jobs will fulfil other tasks outside of these “core” ones. As job responsibilities can vary widely in practice, we believe it is important to promote a role with model evaluation as a core responsibility when deploying AI models

Challenge #1 – Measuring the right things and knowing our limits

For AI to benefit society, we must be able to determine what “good” looks like. An evaluation of state of the art AI performance frequently hinges on single scores using benchmarking datasets. These benchmarks tend to be task-based challenges, such as AIME (high school mathematics) and agentic coding (SWE bench).

Why this matters

These benchmarks make for impressive leaderboards and simplify comparisons, but scores do not necessarily generalise to other tasks, and rarely even come with an estimate of the score’s uncertainty. By overemphasising incremental improvements, we risk overfitting and selecting models that may not be performant outside of that specific task. Having reference datasets on the internet can even end up contaminating the training datasets, decreasing their usefulness as evaluation measures at all. Large language models, interacting through text, can be asked to state their confidence through the “LLM-as-a-judge approach”, but this has been shown to be poorly behaved and potentially misleading – we run the risk of training a model just to fool another model.

Challenge #2 – Understanding wider risks: what’s the worst that could happen?

AI models don’t just live in research labs – they meet people in different settings every day. Understanding how a model fits within its environment requires a wider systems thinking that models complex interdependencies. This skillset spans scales, from the technical minutiae that impact model performance through to the knowledge of downstream results of AI outputs. Robust deployment does not simply consist of technical tasks; it is a critical and dynamic component of an evolving socio-technical ecosystem.

Why this matters

Many modern AI systems choose an agentic design, or one with many repeated calls to an LLM. This is powerful as it allows specialisation, but the long sequence of calls means that small errors can quickly snowball. For example, Visa recently enabled AI models to automatically browse and complete transactions – imagine separate agents looking for products you want, evaluating your financial capability, performing product comparisons, and then pooling information. How can you ensure this system is robust enough to prevent emptying your bank account next time there’s a sale on? Building sufficient guardrails requires an understanding of how all of these agents interact, alongside weighing the potential negative impacts for the end user.

Challenge #3 – Deploy, forget and fail

Machine learning operations (MLOps) handles the broad challenge of whether machine learning models can be trusted in deployment. Errors can come from model drift or from shifts in behaviour, policies, or deployment environments – there’s no one-size-fits-all approach, and it needs deep contextual knowhow.

Why it matters

As statisticians and data scientists take on more responsibility for complex deployed systems, we need to build in more guardrails to help us monitor them. This means understanding the models alongside the deployment context; developers need to own models throughout the lifecycle, with staff members that take responsibility for enforcing high levels of performance and explainability, even when using models they haven’t trained in-house.

Challenge #4 – A voice from the coalface to make the law work better

AI regulation is here. The EU AI Act came into force on 1 August 2024, with legislators around the globe competitively forming policies. The EU regulation formally prohibits some AI activities, such as recognising emotions in the workplace or predicting the likelihood of committing a crime based on personality. The Act distinguishes between AI models (e.g., foundation models like GPT4) and AI systems (applications which may or may not be built upon foundation models), classifying them based on risk and the amount of compute required to train them. Understanding the risk of your application could become a legal obligation.

Why it matters

Although the number of people developing general purpose models that exceed the threshold of 10^25 FLOPs is small, the number of current data scientists and statisticians developing AI systems is growing. The consequences for companies breaking the law could be dire; severe offences can bring fines of up to €35 million or 7% of a company’s global annual turnover, whichever is higher. Community-driven frameworks allow practitioners to define expected practice, such as the broad ISO42001 standard for AI models, or in specific domains, such as ‘FUTURE-AI’ (maintaining fairness, universality, traceability, usability, robustness and explainability) in medicine.

The future

The mass enthusiasm for AI systems has turbo-charged the development and application of the technology. Models are a daily companion for millions of people, and the potential to use the tools inappropriately is growing. Deciding whether to trust new models, and within which regimes, requires a new skillset.

The AI phronestician will be responsible for ensuring AI models are held to account and that they meet the standards we expect – it will be a significant role. This requires a diligent, forensic approach, not to mention the new skills that come with new models. We’re calling on data scientists to take some key actions today that will help us embrace this future, and not stand by while AI happens around us. You may already be doing many of these, but we want readers to feel emboldened when surrounded by so much hype rushing them along the path to deployment. These steps are:

- Challenge AI models used in your day-to-day jobs by pushing for thorough evaluation throughout their deployment. This can mean being a cautious voice, and data professionals need to know there is a community facing similar challenges.

- Strive for best practice, such as with ISO standards or for professional data science accreditation, and encourage feedback to improve.

- Accept that responsibility doesn’t stop once final model weights are calculated. Build long-term, well-understood, reliable systems with comprehensive risk evaluations.

- Use your practical experience to help guide the field – where are the cracks that can let harmful algorithms through?

Crucially, use all of this experience to help us in the statistical community to work together to influence the evolution of AI. Engage with your national statistical society’s AI specialists (such as the RSS AI Task Force, where we advocate at governmental and regulatory level). What skills are you lacking? What case needs to be made more loudly? By doing so, data scientists can advocate at the local level and help mould the profession, taking us towards a better, more robust future with AI.

The authors are members of the Royal Statistical Society AI Task Force.